Long-form exploration of ideas about certain topics. These are usually complete bodies of work and are supported by extensive research and introspection.

I watched a documentary once about people who had lost a limb. Apparently, it is common knowledge that many amputees can feel their lost arm or leg. In some instances, they can even feel pain from the limb that is no longer there — this is called phantom limb pain. Even if you throw a ball at an amputee’s lost arm, for instance, they will instinctively try to catch it with their phantom arm. Of course, they adjust eventually, but the feeling and awareness never really go away. I often wondered about this phenomenon. Is it the same mechanism that drives us to yearn for people we’ve lost?

A recent study in neuroscience suggests that our brains create a virtual representation of ourselves and our environment – just like the Matrix. What we experience as reality is actually a constructed representation using our five senses, memory, logic and intensions. In addition, our representation of the world gets reinforced the more we experience the same thing. And at the same time, our brains can reconstruct our sense of reality to suite our present situation or intentions – like valuing food more when we are hungry. Even more interesting, our brains can create an entirely new reality without us knowing, and we experience it as a matter of fact. This leads us to a fundamental insight, which is that the world is necessarily different from what we think it is because our perceptions are ever-changing constructions.

Since our perceptions are malleable, they necessarily lag behind reality. Like a dog’s tail, when something changes in the “real world”, let’s say, our perceptions follows suite, albeit after that fact. For this reason, when we experience a big disruption such as losing a limb, a loved one or a job, it takes time for our brains to reconstruct the new reality because our perceptions rest on heavily reinforced experiences. Incidentally, this disruption and reconstruction process is what we experience grief. If we are to use Kübler-Ross’s five stages, it begins with denial. I guess denial is the stage where the new reality is at odds with our representational reality, and we simply refuse to accept that things have changed. Accordingly, we eventually accept the change, albeit after a while.

But I find Kübler-Ross’s five stages somewhat incomplete. Having lost my father 15 years ago now, I cannot really say I have reconciled myself with that fact. There is something about the thought of him that elicits a deep sense of yearning, especially around significant times of the year, such as his birthday. I still talk to him as if he were sitting next to me even though I know, rationally and physically that he is not here.

Perhaps there is some truth to the philosophical idea that personhood is different from humanhood. In his book, On Human Nature, Roger Scruton explored the idea of personhood as emerging from humanhood. By way of analogy, we can look at how a melody emerges from sound. As we know, sounds are merely movements of air at various frequencies. But when the sounds are carefully arranged, they can transport us instantly to a lovers arms, mom’s kitchen when the air was aroused with the smell of scones, or childhood memories with friends watching a scary movie for the first time – such is the power of a melody. What was merely the movement of air has become a thing in its own right that lives in the mind devoid of its physical origin. Like a melody, Scruton argued, a person emerges from the human – or the physical complex of flesh and bones – and becomes immortalised in the hearts and minds of others, long after one has physically departed.

As a side note, I just finished writing an app that allows you to send messages to loved ones after you have passed away. Read more about it here.

All the cultures around the world have grappled with this idea of humanhood and personhood, flesh and spirit, or what is sometimes called the mind-body problem. In the process of exploring different ideas, their civilisations inadvertently evolved and became identifiable as a mosaic of beliefs and cultural practices. Zen Buddhists and Taoists, for instance, believe in living in the moment and not clinging to the past nor the future. In their world, life is centred around the well-being of one’s humanhood (as it were) and how we harmonise with our environment. In service of this idea, meditation is a tool for bringing the mind back to the body to live in the present moment, unencumbered by attachments and desires. Contrary to many misconceptions, meditation is not a tool for escaping reality, it is a means of coming back to it.

As a member of the Ndebele nation in South Africa, a branch on the Nguni tree of people, we believe the body is animated by a spirit. What I referred to as personhood emerging from humanhood is not compatible with this way of looking at the world. Instead of a person emerging from the flesh, the person (or spirit) exists in its own right as a sovereign entity and manifests itself in the physical form. In a sense, the spirit is a trans-material entity, able to live in the spiritual plane and simultaneously descend to this world and conjure with the flesh. To this end, our bodies are like musical instruments that resonate or connect to certain frequencies, if you like, of the spiritual plane. Likewise, people (just like instruments), are different and therefore possess varying degrees of sensitivity to the other world. Hence, it is believed that some people have more access to the spirit world and are therefore given the responsibility of keeping us in touch with it.

Interestingly, Christianity (as a creationist doctrine) has yet another view of how we are constituted. Creationism presupposed that the world came into being from or by virtue of an original force or God. Furthermore, as per Genesis 1:26, we were endowed with free will, which allows us to carve our destiny in this world. Incidentally, free will disconnects us from, let’s say, the will of God because one cannot wield their will freely and be tethered at the same time. But to keep us in check, we are promised that one day we will be ushered to a permanent resting place representative of our deeds in this world. Nevertheless, central to this doctrine is the notion that we are humans (flesh) with the power to choose the spirit to imbibe. The spirit we choose becomes part of what emerges from this flesh to live in eternity, either in heaven or hell.

It goes without saying that I have omitted many other cultural ideas in this brief discussion. My aim was not to canvas and catalogue the world’s views of what we are, but to briefly explore the nature of humanhood and how it differs from personhood (or flesh and spirit) according to the major cultures that influence society today. Therefore, by way of a summary, the Christian view posits that we were created to rule and lord over the world. Yes, there are moral ideals and consequences – and there is no shortage of exemplars in the form of saints or even Christ Himself – nevertheless, each person remains free to exercise their will to whatever ends. On the other hand, Buddhists and Taoists are economical about spiritual ideals, especially given the immediate and often difficult task of having to live in this world. Hence, they advocate presence and harmony with the world. For the African, people never really die; when we leave this form, we remain accessible as active ancestors whose spirits can summon the flesh.

It is within this context that I draw compatibility issues Kübler-Ross’s idea of loss or grief. For Ross or the Western-Christian mind, if I may venture to be so gratuitous, we live on borrowed time and once we are done here we never come back. Hence, one must reckon with loss and eventually accept that what is gone is gone. For an African child such as myself, my father’s spirit is well within my reach. Sometimes we speak through dreams, and at other times I see him through events, people or things that happen fortuitously. The death of a loved one, therefore, does not end with acceptance. On the contrary, it serves as a reminder that one is connected far beyond the happenings of this world.

In the film, Man of Steel, there is a scene where the young Superman is in a classroom, and suddenly gets overwhelmed by his sensitivity to the world. He hears distant and even the most minute sounds – the clock ticking, sirens blazing, hearts beating, and even the sound of pencils scratching on paper. He sees food digesting in people’s stomachs, eyeballs rolling in their sculls, lungs inflating and deflating, and the clamour of his classmates’ sinister thoughts. Eventually, he storms out of the classroom, locks himself in a storeroom and covers his eyes and ears, hoping to silence the avalanche of information. Finally, his mother arrives, and he cries out to her, saying, “The world’s too big mom.” To which she replies, “then make it smaller.”

The irony is that the human mission is to make the world bigger – to break out of our biological limitations, as it were. In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave[1], for instance, Socrates paints the picture of prisoners who, since childhood, are chained to the bottom of a dark cave. Their limbs and necks are shackled so that they cannot move. Behind the prisoners, a wall shields them from seeing anything except the wall in front. Above and further back, a fire illuminates the cave and the light shines on the wall ahead of the prisoners like a projector in a movie theatre.

Then, Socrates imagines people walking with figurines between the fire and the wall behind the prisoners, thus casting shadows in front of them. Bearing in mind that the prisoners have been chained there since childhood, their only conception of reality is the shadows that appear before them. The prisoners even interpret the feet shuffling behind them as coming from the animations on the wall – a kind of surround sound system if you will. As the allegory goes, the prisoners even develop strong feelings and beliefs about the different types of images they see, unaware that they are mere projections from a fire behind them.

Amazingly, this allegory was imagined more than 2000 years ago. Today we attend movie theatres, and even though we know that the film we are watching is not real, we nevertheless get taken in. We laugh, cry and even chant for the good guys, only to be rescued back into reality when the movie ends. This is a metaphor for our conception of reality. In the same way that the projection of shadows enthralled prisoners, and we are taken in by movies, our vision is similarly a reflection of light from objects into our eyes. Likewise, our eyes can only see a narrow spectrum of light compared to what actually exists – and the same applies to all our other senses. Needless to say, we consider everything we experience fundamentally real even though it is only a slender interpretation of reality.

It is from these biological and other limitations that scientists, philosophers and artists of all stripes have sought to break us out. Today, our tools help us see further, and travel faster; we are even immortalised on social media and YouTube. The byproduct of these advances, however, is that we are inundated. In some sense, we have arrived at the terrible realisation that the world is too big. However, there appears to be nobody encouraging us to make it smaller. Instead, the unspoken narrative is to make it even bigger. To add more.

Fifteen years ago, I was fortunate to build tracking systems for cars. At the time, GPS was a relatively new consumer technology, and the idea that one could locate their vehicle on a computer, let alone a phone, was astonishing. The way GPS works is relatively simple. There is a constellation of satellites orbiting the earth more than 26,000km away.[2] When your phone tries to find a location, it connects to as many satellites as possible, which in turn respond with a signal relative to where they are. If the device cannot connect to more than four satellites, it reports a signal error. A good signal is usually eight satellites or more.[3] The more satellites, the more precise the location becomes – up to one metre.

In the same way that satellites improve location, attention improves our experience of reality. But what happens when attention is compromised? Our attention, nowadays, is pulled in multiple directions at any given moment. While eating, we are listening to music, watching television, writing emails and possibly stalking people on social media if not watching a movie. Therefore, the quality of our experience is greatly diminished; only one or two sensorial satellites, as it were, contribute to what becomes a partial experience (of eating, for instance). Thus, our reality is further diluted. This dilution is, of course, praised as our ability to multitask. The truth, however, is that we are robbing ourselves of the richness of experiences.

The way we perceive the world, therefore, has changed. Our ancestors did less but experienced more; we are doing more but experiencing less. Be that as it may, our biology has not evolved to account for this change. Therefore, the thirst and hunger for high-intensity experiences follows us as a shadow of dissatisfaction, boredom and loneliness, even though we are seemingly busy and endlessly preoccupied. We are fed but not nourished.

Spirituality appeals to us by offering an antidote to the dilution of experience. The spiritual path demands putting things down and reconnecting with one’s senses – at least as a first step. Having put down worldly contrivances, we are encouraged to take further ascetic steps by suppressing our desires for sex and food. In some Buddhist schools, for instance, inhibiting pain is celebrated as a milestone in spiritual development. This was put on full display in Vietnam in 1963 [4] when monks, protesting ill-treatment from the government, occupied the street and one immolated himself, marking a turning point in the history of Vietnam. In other spiritual schools, people fast until they are completely emaciated – they mummify themselves in the name of attaining spiritual awakening. The spiritual need of putting the world down, it seems, has its bizarre extremes as well.

Nevertheless, spirituality strives for transcendence through asceticism. That is to say, by suppressing our basic instincts, and in some sense, giving up who we are with the promise of discovering who we really are. On the other hand, technological innovation, and dare I say modernity, also strives for transcendence, although by challenging or even breaking our biological limits. Both paths appear to be destined for somewhere other than where we are. They both seem to say there is something wrong with where we are that we must find a sense of meaning elsewhere.

A Darwinian might argue that nature is always evolving, albeit slowly. Therefore technology only moves evolution faster! In other words, there is nothing wrong with breaking our biological limits because nature would have done that anyway, although slower. Of course, there are many questionable presuppositions about this point of view, but their justification for transcendence (or going beyond where we are) is that it is inevitable.

On the other hand, platonic idealists would argue differntly. For them, there is a perfect form to which all things aspire. The purpose of this life is to strive for perfection, or to realise our ideal. In the same way that Christ sacrificed himself in this life and became one with the Father, we too ought to sacrifice ourselves by subduing our deficiencies, and in so doing make a case for a place in heaven (or the forms). Therefore, they also support an idea of transcending, at least insofar as it brings us closer to perfection.

Existentialists might argue that the world is inherently harsh, and chaos beckons. Innocent children die, good people fall ill, natural disasters are amoral, and the clouds of evil always linger behind twinkling eyes. Therefore, there is no point in holding naive views or ideals; the meaning of life is not to be found in some ideal. Rather, it should be created by each individual by taking on the burden of responsibility for their life — by choosing to create order in a world of chaos. In this regard, responsibility is the means by which one transcends a naive sense of the world — it is the sense by which one effectively grows up!

While these perspectives are not exhaustive, they all appear to find faults or inadequacies in our present form — they prescribe some improvement, one way or another. Thus, the consequence that we are at loggerheads with ourselves as we are, and the antidote is transcendence in some form.

In 1903, Ralph Emerson made a similar case in his essay titled, Nature.[5] He remarked that “nature, in its ministry to man, is not only the material but is also the process and the result. All the parts incessantly work into each other’s hands for the profit of man. The wind sows the seed; the sun evaporates the sea; the wind blows the vapour to the field; the ice, on the other side of the planet, condenses into rain; the rain feeds the plant; the plant feeds the animal, and thus the endless circulations of the divine charity nourish[es] man.”

Even though nature serves us, Emerson nevertheless laments our blind dissatisfaction. He complains that, for whatever reason, we scrape the earth and pave it with railway lines. “Mounting a coach with a ship-load of men, animals, and merchandise behind him, man darts through the country from town to town, like an eagle… By the aggregate of these aids, how is the face of the world changed, from the era of Noah to that of Napoleon!” — how we have made the world unbearable by trying to make it more habitable.

As an antidote to man’s madness, Emerson prescribes solitude. He adds that even reading a book ought to be prohibited when in solitude. After all, books raise questions for which nature possesses answers. Solitude means walking amongst the trees and listening to the gentle breeze gossiping with the leaves. It means swimming in a river, feeling the pebbles at the bottom of the riverbed and allowing ourselves to be carried away by the current. And in the evening, it means gazing at the stars, the envoys of timeless beauty that remind us of the city of God.

Oh, Emerson! If not from nature’s wrath — earthquakes, hurricanes and volcanoes, or violent beasts — then it is certainly from the demands of everyday life that one is rudely awakened from this paradise.

On the one hand, we enhance ourselves to contend with the demands of the world. On the other hand, we feel a deep pull towards putting things down and replenishing our souls. The material world is at war with the spiritual and the prevailing logic is that we must choose one side over the other. We must either choose to be rich and miserable or enlightened and poor. I contend, however, that this is hardly a way to lead a wholesome life. There must be another way.

For starters, intelligence is the instrument we use to make a living in the everyday, practical world. Consider an unemployed person, for instance, who is tormented by purposelessness and the need to find oneself. At the core, they are actually looking for a niche in the practical world where they can make a contribution. Hence, when they find an occupation, their thirst for purpose temporarily goes away. Then, once they become comfortable in that niche, the nagging question of purpose returns, albeit at a higher level this time. Only this time, the answer can no longer be found in the everyday, material world. Instead, the yearning comes from the spiritual world.

The spiritual world, however, is different from the practical world because intelligence and utility have no place over there. This idea is not new. It was somewhat captured in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, but more beautifully by the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. A famous Zen Master, Hakuin Ekaku, sought to solve this problem by offering kōans to his students – riddles that cannot be solved with logic.[6] These included questions like, “what is the sound of one hand clapping?” A monk could not graduate until they found an answer. Needless to say, some of the responses were just as bizarre as the questions. Kōans were tools to cleave the mind from its fixation on logic. They were a way of leading the student to a different world which is better described by the Japanese word Yügen, or the Christian word, Grace. Sir Roger Scruton, an accomplished British philosopher, might have called it Home.

The thirst for a higher purpose, therefore, is not quenched by instrumental thinking. In an Emersonian sense, it is in the realisation that nature works charitably in service of our well-being that perhaps a clue hides. Therefore, instead of fighting, sometimes we can and probably should put down our weapons of intelligence and replenish our souls with the splendour of nature. Even in tragedy, such as watching a lion tearing into the flesh of a young gazel while its mother watches helplessly, somehow we find redemption in knowing that nothing in nature goes to waste. Therefore, violent as nature might be from time to time, we always return to it in search of a kind of cosmic hug or a sense of Home. Perhaps this is what we are truly yearning for…

In one sense, the human condition is characterised by our limitations. We neither possess fangs to kill nor thick fur to keep ourselves warm in winter. Our intelligence allows us to create these extensions out of the remnants of nature – this is essentially what technology is, a need to complete ourselves. As we augment ourselves, however, we depart from who and where we are and slowly grow weary. Then, when we become tired of wrestling with the world, we develop a deep yearning to put things down and follow a spiritual path of replenishment. If we continue along this path, we may fall into yet another trap of suppressing our feelings and instincts, which is also a departure from who and where we are.

This way, we find ourselves pendulating between the material and the spiritual worlds in search of meaning and purpose. However, with this to-and-fro comes a different yearning, a yearning for rest or to be at home with oneself. But consider this: a boiling cup of tea cools down. A block of ice, left alone, warms up. Is it therefore possible that the path home requires that we surrender to the world as it is?

…like a cup of tea?

[1] Plato, The Allegory of the Cave. Brea, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2010.

[2] Federal Aviation Administration, “GNSS Frequently Asked Questions – GPS,” Apr. 23, 2020. https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ato/service_units/techops/navservices/gnss/faq/gps/ (accessed Sep. 23, 2020).

[3] Strava, “Why is GPS data sometimes inaccurate?,” Strava Support, Jan. 12, 2019. http://support.strava.com/hc/en-us/articles/216917917 (accessed Sep. 23, 2020).

[4] R. F. Worth, “How a Single Match Can Ignite a Revolution,” The New York Times, Jan. 21, 2011.

[5] R. W. Emerson, Nature, Addresses and Lectures. Houghton Mifflin, 1903.

[6] Shambhala Publications, “Hakuin Ekaku: A Reader’s Guide,” Shambhala, Apr. 26, 2017. https://www.shambhala.com/hakuin-ekaku-c-1685-1768/ (accessed Sep. 23, 2020).

According to an article by the British Chamber of Commerce (2015)[1], companies are disappointed with the quality of young candidates entering the job market. Even when searching Google for articles relating to millennials and the job market, one inevitably comes across the sentiment there are issues. For starters, millennials, or the me-generation, as they are called, are said to have entitlement problems, often believing they are worth much more than they deliver. They are self-centred and motivated by passion rather than reason and common sense. One blogger wrote that millennials lack the Protestant Ethic, the old tradition of working your hands to the bone just for a chance at creating a meaningful life (Fletcher 2014)[2].

This notion of millennial impotence appears to be supported by mountains of unemployment data. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2017)[3], youth unemployment is significantly higher in both developed and developing countries as compared to their national averages. For instance, the youth unemployment in the U.K was 11.4% in 2019, more than four times the national average of 2.7%. In the U.S, the phenomenon is the same – youth unemployment in 2019 was 8.4%, almost three times the national average of 3%. The South African unemployment statistics are jaw-dropping but present a similar statistical reality, with a youth unemployment rate of 63% against the backdrop of a 30.1% national average (StatsSA, 2020)[4].

We can conclude, therefore, that search parties are out. Policymakers around the world are desperately looking for solutions to curb youth unemployment. And companies are looking for ways of improving their productivity levels from people. So far, the media and large economic institutions are wagging their fingers at schools and blaming them for failing to produce economically viable individuals. For instance, the World Economic Forum (WEF) published a report titled “New Vision for Education: Unlocking the Potential of technology”[5] – a decree, as it were, that outlines what schools ought to do to get their act together.

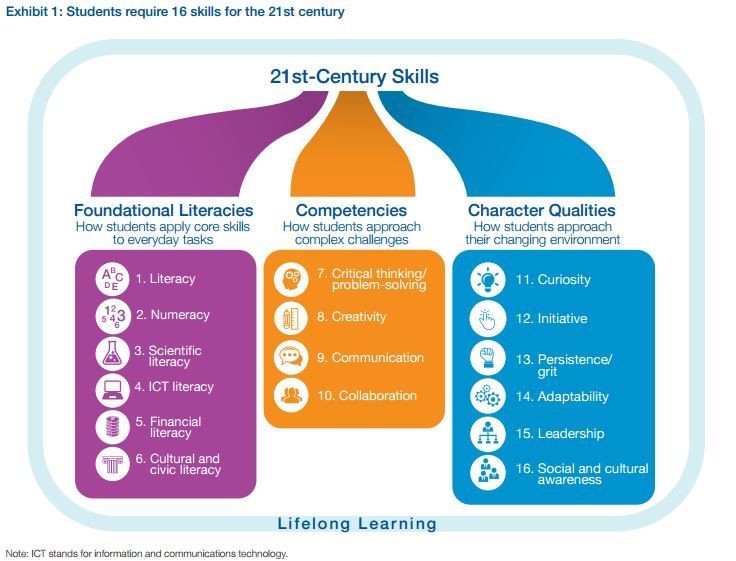

The report identifies 16 skills deemed “critical” for the 21st century, as shown in figure 1 above. The further report declares that the WEF surveyed 100 countries and found gaps in the extent to which schools readily produce individuals with these skills, and as expected, they claim that developed countries do a far better job.

To remedy this problem, they developed an underwhelming model called the Closed Loop, where a team of educationists work together, firstly to determine learning objectives. After that, they compose a curriculum, which becomes a scripted manual for teachers to deliver instructions. Then, with the help of technology, they continuously assess the learners and provide tailored interventions to help them succeed. The report concludes with a catalogue of recommended software and case studies for implementing the Closed Loop model – a sales pitch masquerading as a report.

1.

To truly appreciate the scope of creating a vision for the future of education, it is necessary to begin by briefly scanning the annals of history to contextualise our present relationship with learning. Throughout the ages, the nature of education has always changed in accordance with the intellectual fashions of the times. For instance, Plato and Socrates, who lived between 428 and 322 BCE, established the idea of idealism, which is the notion that there is a perfect or ideal version of all things. Consequently, our pursuit of knowledge or betterment is actually a search for the ideal. In other words, when we work towards something or improve ourselves, we are merely moving closer to a pre-existing, albeit a more ideal version of that thing or ourselves. Take, for instance, learning music. We start off without knowledge and sturdily become better as we practice – or as we move towards the ideal.

Interestingly, the side effects of idealism manifested most prominently in the study of medicine. Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine and a contemporary of Plato and Socrates, held a similar view. To him and his followers, illnesses were a kind of intrusion that caused an imbalance in the body. In other words, the body has an ideal state, which we experience as being healthy. They reasoned, therefore, that there must be physical causes of illnesses and that the correct diagnosis could lead to the right remedy. That was a revolutionary thought in a world steeped in alchemy, magic and the supernatural. Nevertheless, in the spirit of idealism, the Hippocratic school of thought held that diagnosis ought to be strictly observational and non-intrusive, lest one worsens the body by prodding, introducing foreign objects and further besmirching it from the ideal. As it turns out, that rule of non-intrusion contributed to a monumental setback in the advancement of medicine.

In John Barry’s masterpiece, The Great Influenza, he cites that it took 2000 years (with blips of advancement here and there) for the medical world to truly break this Hippocratic hangover. [6]Only in the 18th and 19th centuries, when a different school of thought gained traction, did physicians find the courage to dissect, prod and probe the body to understand how it works and discover what could otherwise never be known, such as microorganisms like bacteria and viruses. In this regard, we can see how idealism, as an underlying school of thought, precipitated an epistemological blind spot in the medical world. Furthermore, this example shows how philosophies can manifest into advances and limitations for education and what we believe can and ought to be known.

This understanding, therefore, beckons the following questions. What are the philosophical underpinnings of our times? And how are these ideas manifesting themselves in our relationship with education? Only by first answering these questions can a vision for the future of education, in earnest, be crafted.

2.

While we are still enjoying the fruits of the Enlightenment and the pre-Enlightenment ages, we are currently in a new intellectual age. The post-modern era, as it is called, is anchored by new assumptions about how the world works, and the consequences will be no different from the introduction of idealism in 500bc, rationalism in the 17th Century, and existentialism in the 20th Century. Our times will similarly precipitate new advances and limitations in our understanding of knowledge and what ought to be known.

To begin with, today people are more empowered to service their self-interests more acutely than ever before. People are empowered to adopt beliefs and values that are not prescribed by the culture that underpins their biological or geographic origins. Instead, we can reach into the virtual cosmos, as it were, and find other, more resonant communities and people. Manuel Castell, a professor at the University of Southern California, calls this process individuation, following Carl Jung’s postulation that a wholesome person is one who has discovered and come to terms with all aspects their being; one who can resist mass-mindedness, especially the kind that was prevalent during the height Marxism and Nazism.[7] Castel argues that “…there is a shift toward the reconstruction of social relationships, including strong cultural and personal ties that could be considered a form of community, based on individual interests, values, and projects.”[8]

Given Castel’s arguments, however, it is also worth noting a 2017 report from the World Health Organisation (WHO) citing more than 300 million cases of depression and anxiety, seemingly a new psychological epidemic of our times.[9] Some scholars attribute this new wave of depression and anxiety to narcissism – a byproduct of Castel’s hyper-individuation, one could say. In his book, Individuation and Narcissism, Mario Jacoby points out that blindly pursuing self-interests can lead to the notion that happiness is (in a platonic sense) an ideal that ought to be chased at whatever cost.[10] In the feverish pursuit of happiness, it follows that ideas that appear to differ or threaten one’s happiness ought to be irradiated. Ultimately today’s intellectual horizon, supported by the ease of finding in-groups, and the significantly low cost of slandering and provoking others behind the veil of the internet promotes intolerance and anxiety amongst people and communities with seemingly different objectives or ideals.

3.

With this basic understanding of the intellectual mood in which we live, we can now turn towards education. Even though education has changed throughout the ages, the promise of passing down valuable knowledge for the next generation to survive and thrive remains constant. As it stands, we live under the influence of three major intellectual epochs: the pre-modern age, which is characterised by the belief in gods, providence, miracles and alchemy; the modern age, where rationality and the power of the mind to change the world replaced our eternal patience for God’s intervention; and the post-modern era – where we believe we are the centre of the universe. These intellectual personalities, as it were, are all fighting for a share of our minds.

From this perspective, we can appreciate the overwhelming difficulty of trying to manage, let alone conceive a comprehensive system for the future of education. Nevertheless, the question that ought to underpin any grand vision for the future must respond to these complexities as effectively as Horace Mann did for American schools during his time. Mann is widely regarded as the father of the schooling system as we know it today. He is remembered for envisioning and transitioning schools from being strictly religious i.e. belonging to the pre-modern age, to becoming more secular and having a national reach, in keeping with the transition from Monarchs and churches, to constitutional democracies.

In this regard, the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) vision tries to follow in the footsteps of Mann by advising and even referring to technologies that offer tailored learning pathways. Indeed, this is an inadvertent response to Castell’s observation of individuation. But what is confusing about their vision, is that it also promotes the central development of scripted curricula.

The first challenge with this approach is that if learners have access to the internet, they will have access to the best teachers worldwide, making prescribed curricular and scripted lessons obsolete. A second, more fundamental problem is the assumption that a central committee knows what should be learned in the 21st century. At with dawn of the Enlightenment era, disciplines emerged spontaneously out of curiosity rather than dogmatic promulgation of preconceived curricula. Similarly, the modern, individuated child is spontaneously learning new disciplines such as podcasting, video editing, artificial intelligence, blockchain and other technologies without the aid of formal education. If there is anything to learn from history, it is that the current notion of preconceived curricula runs the risk of shrinking into obscurity, as did the pre-enlightenment religious schools.

The WEF’s report is not entirely flawed, however. Basic skills, such as literacy and numeracy have rightfully enjoyed a degree of importance in their report. In addition, the report extends the catalogue of what they consider literacy by including ICT literacy, financial literacy and cultural literacy. Regarding their Competencies category – that being critical thinking, creativity, communication and collaboration – they are misappropriated as 21st-century skills. These are old skills whose use advanced the frontiers of humanity throughout history. Their third category, what they call character qualities, including leadership, adaptability, grit and curiosity, call for more scrutiny.

For years psychologists agonised over understanding personality. Today, there are countless frameworks that promise to help one understand who they are. Nevertheless, all of them hinge on a long-standing assumption that we are born with different personality dispositions. In other words, what the WEF refers to as Character Qualities, are better understood as personality traits that develop naturally with varying degrees in different people. An entrepreneurial person, for instance, will show grit, leadership and adaptability. In terms of the Big Five Personality Traits [11], their entrepreneurial disposition is a result of scoring highly in Conscientiousness, Openness To Experience, and Intellect, while scoring low on Neuroticism. More importantly, these are traits that influence what one prefers learning, or which skills they would rather acquire. Hence the WEF understanding of Character Qualities is misplaced because they are really referring to personality traits that occur naturally and in varying degrees amongst people, rather than skills that can be learned.

Unfortunately, the report is silent on the most significant intellectual malaise of the post-modern era, that being narcissism, depression, anxiety and intolerance. It could be that the notion of Character Qualities, although misplaced, was the WEF’s attempt to capture the essence of this post-modern problem. Even if that were the case, the problem of understanding oneself and building character is ancient. For instance, all cultures have some form of what I will loosely call “the rites of passage”. The English had fraternities such as scouts, where children learned cultural values, respect, teamwork and the like. Africans and some Asian cultures take young boys and girls into seclusion to teach them about their origins, values, poetry and history. All these are efforts at developing character qualities. Hence, I contend that developing character is an old problem, and the WEF has once again misappropriated it as a 21st Century skill.

4.

Given the enormous task of crafting a vision for the future of education, the WEF’s report is economical in sophistication. It bends towards propagating a system, the Closed Loop, which is simply a new label for the current curriculum-based education system with a lick of technology to mend the cracks. The report makes a mild attempt at capturing the need for universal literacy but of course, universal literacy is an old idea that was promoted by the ilk of Horace Mann in the 19th Century. Furthermore, the report misappropriates personality traits as skills and fails to deal with today’s biggest psychological challenges, emanating from our changing cultures, adoption of technology and hyper-individuation.

We live in altogether different times. While businesses are finding it challenging to work with millennials and younger people, it is also worth noting that millennials, the internet-driven generation, are finding it equally difficult to work with traditional businesses. Therefore, instead of wagging fingers at the education system to manufacture proper humans, it is more sensible to appreciate the intellectual era we live in because it influences our relationship with learning. Among others, people are no longer satisfied with dedicating their whole lives to working for one company. Instead, people are learning new and more complex skills, of course, as part of their journey on the individuation path. In addition, people are looking for new ways of dispensing with their skills in more intimate ways rather than as a cog in a large cold company.

My position is that we ought to accept individuation as a more prevalent cultural phenomenon. In other words, the sovereignty of the individual is rising, and policies that wish to cling to archaic hierarchical systems, rather than new networked social systems will fizzle into irrelevance, as did the monarchies and the churches as the Enlightenment age gained traction.

[1] BCC, 2015. BCC: Businesses and schools ‘still worlds apart’ on readiness for work [WWW Document]. URL https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2015/11/bcc-businesses-and-schools-still-worlds-apart-on-readiness-for-work (accessed 8.24.20).

[2] Fletcher (2014) Why Youth Are Unemployable, Adam F. C. Fletcher. Available at: https://adamfletcher.net/why-youth-are-unemployable/ (Accessed: 24 August 2020).

[3] OECD (2017) Education at a glance: Transition from school to work (Edition 2017). Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/data/19558ffb-en.

[4] Africa, S. S. (2020) ‘Vulnerability of youth in the South African labour market | Statistics South Africa’, 23 June. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13379 (Accessed: 13 April 2021).

[5] World Economic Forum, “New Vision for Education: Unlocking the Potential of Technology,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://widgets.weforum.org/nve-2015/.

[6] J. M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Penguin, 2020.

[7] C. G. Jung, The Undiscovered Self: The Dilemma of the Individual in Modern Society, Edition Unstated edition. New York: Berkley, 2006.

[8] M. Castells, “The Impact of the Internet on Society: A Global Perspective,” OpenMind, 2013. https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/the-impact-of-the-internet-on-society-a-global-perspective/ (accessed Aug. 26, 2020).

[9] World Health Organisation, “Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates,” 2017. Accessed: Aug. 26, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf;jsessionid=3C066D350D7C8E8630F9F3DF6844E976?sequence=1.

[10] M. Jacoby, Individuation and Narcissism: The psychology of self in Jung and Kohut. Taylor & Francis, 2016.

[11] A. G. Y. Lim, “The Big Five Personality Traits,” Simply Psychology, 2020. https://www.simplypsychology.org/big-five-personality.html.

During the early 1900s, there was a problem in the music industry. By and large, people were using gramophones to listen to their favourite songs. But the technology only allowed for approximately four minutes of playback, and the quality was awful: the high notes from flutes and violins, together with the low notes from the tuba or the base were either distorted or barely audible. Incidentally, this gave rise to the four-minute-long pop music that we are familiar with today, where the prominent feature is the human voice.

The main grudge, however, was that people could not listen to classical music, which is much longer and has a broad range of sounds. As you can imagine, the pursuit of a solution became an obsession for scientists and record labels of the time. In 1948, there was a breakthrough. Columbia records transformed the industry by introducing the Long Play record, the LP as we know it today, allowing studios to record up to 40 minutes of high fidelity sound. The technology quickly became the new standard for distributing music. And finally, it was possible to capture a full-length piece of classical music with all its dynamism in a single package. Then, popular music, most notably jazz, became longer and more lyrical. In cases where the music was shorter, multiple songs were strung together in a singled LP, and thus the album was born. In the years to come, the album became the key performance indicator; the more albums sold, the more successful an artist was regarded.

A few decades later, in the 80s, the Compact Disc (CD) was introduced, and the length of the album doubled to 80 minutes. The more significant change, however, was in the quality and format of the music. For the first time, sound became quantised – it was turned into data bits that could be manipulated after the recording. Therefore, having recorded a song, an engineer could play with the various frequencies to enhance instruments or textures that complement the human ear.

Interestingly, our ears are tuned to listening to people’s voices or sounds in that range. As a result, lower frequencies are more difficult to hear, and high notes can quickly become unbearable. For this reason, sound engineers, during the 90s, started reducing the loudness of the high tones, while increasing the volume of low notes to optimise music for the human ear. It was a bit like removing all the food you do not like from a platter and replacing it with your favourites. It worked. This practice became known as dynamic range compression. Ultimately, old music was remastered to fit this new fashion. People bought high-fi systems with an endless array of knobs, switches and dials to further sharpen the sound. Speakers became more sophisticated, clearer and, of course, much louder. In a way, this gave rise to the Sunday Session – you know – that neighbour that hauls out his massive speakers on Sunday and plays soul music and jazz for everybody to hear.

Today, streaming is a new way of distributing music. And once again, music is changing. During the era of the LP and the CD, musicians were paid for every album they sold. Therefore, the musical canvas, as it were, was 40, then 80 minutes long – it kept growing. Today, however, musicians are paid a royalty every time someone listens to a song for more than 30 seconds. Therefore, there is no incentive for creating a long, 10-minute jazz masterpiece, let alone spending years on a two-hour-long symphony. Instead, there is a new surge of three-minute-noodle songs, and even the structure of the music itself is changing. According to Nate Sloan[1], a musicologist, a lot of new music begins with a hook or a hint at the chorus so that you can stick around long enough for the 30-second mark. It’s a shame.

All in all, chart-topping music today is both shorter and louder. Music has become something of a pornographic quickie; it promises a fast release rather than a slow kneading, making and transcendence of time and space. Sir Rodger Scruton shared a similar sentiment in a film on the desecration of beauty[2]. In the video, he laments the mindset of American architects such as Louis Sullivan. Sullivan proclaimed that “form follows function” – in other words, utility ‘trumps’ all other considerations. As a result, 20th-century architecture degenerated into blocks of concrete and steel… nothing like the old citadels, the cobblestoned streets, timeless country clubs and the stories told by curves and creeks in ancient chapels – definitely nothing like the pyramids.

This utilitarian credo appears to permeate modern music, the arts and other areas of our lives. For instance, the arrangement of contemporary music clearly prioritises fun, sex, money, and dare I say, nothing more. There’s hardly any music that captures majesty, tragedy, awe and other subtle human conditions. There is a documentary on Netflix called Liberated: the new sexual revolution, which eerily depicts the same phenomenon of dynamic range compression, albeit in sex – the commodification of sexual intercourse as it were. And if you think about it, we all drive or aspire to drive the same cars. We eat the same food, our idea of fun is more or less the same. The music sounds the same. Politics are the same. Life itself appears to be compressed into a test tube or a petri dish where everything is accounted for and created to make sense.

But I also think the air is brooding for transcendence–the longing to pick up pebbles alongside a shallow stream; the toil of learning a new musical instrument. The madness of working on a life-long project with no purpose, except for the possibility of catching glimpses of oneself; sleeping under the moonlight and the stars on a warm summer night; bursting into uncontrollable laughter; whistling to a beautiful tune. Climbing a tree to reach for the last bundle of fruit right at the top – and maybe even crashing down, and living to share the story of broken bones and scars.

There is no material utility or intellectual meaning in any of this. Yes, we can deconstruct music into chords, keys, notes and other taxonomies. But this does not explain why some music, even though it bears known structural features, evokes feelings of nostalgia and transports us into other dimensions. On the other hand, music that is created in the strictest sense according to best practices becomes kitsch, lifeless and boring. It seems that beauty, art, love and other such spiritual matters exist outside the avenues of intellect, but well within the city of being.

In a way, this makes sense. Through intellect, we download our spirits into the world to make nail clippers, pencils, combs, roads and other such contrivances. Beauty, art and music, on the other hand, appear to upload into and replenish the spirit. When the pursuits of livelihood empty us, where else can we turn for solace, except to retreat home and sink into a warm tub of meaningless – a kind of meaninglessness that is beyond meaning, not devoid of meaning? How else can we mend our broken hearts if not through art? And how can we find consolation for living in this wretched world where an endless number of dangers, many of which are disguised in pleasure, threaten to do us in – in one way or another?

Oh, dear artist, you are the keeper of our souls. Through you, we rediscover the essence of our being, we replenish our spirits and maybe even find the reason for being. Certainly, most certainly, this cannot be done in 30 seconds. The industry is locked in the prison of utility, in optimising things at whatever cost. Do not succumb. The music industry got it all wrong.

[1] Z. Mack, “How streaming affects the lengths of songs,” The Verge, May 28, 2019. https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/28/18642978/music-streaming-spotify-song-length-distribution-production-switched-on-pop-vergecast-interview (accessed Aug. 17, 2020).

[2] L. Lockwood, “BBC Two – Why Beauty Matters,” BBC, 2009.

Subscribe to a weekly dose of ideas about strategy, ethical leadership and innovation.