In this sketch, I observe that high-impact relationships, like priesthood or marriage, are governed by vows or tenets. I observe, however, that although entrepreneurial relationships are impactful insofar as livelihoods depend on an entrepreneur’s success or failure, vows and tenets are nevertheless absent. In light of this, I imagine and propose vows that an entrepreneur might hold as sacrosanct in pursuing and realising their mission.

I arrive at the first two tenets by abductive reasoning, drawing on what I posit is the telos of entrepreneurship. That is, I conjecture that entrepreneurship is about x. If this is true, it follows that to realise x, one must hold y as sacred. However, I realise that the proposed precepts have ethical weaknesses. After surveying a few dominant theories, I settled on Ubuntu as a framework that I use to construct a third and final vow. Therefore, I present three vows and propose that a person so-avowed is not only an entrepreneur but an African Entrepreneur. Finally, I explore these vows in the South African context, mainly along the dimension of inequality, where I speculate on what the African Entrepreneur might do.

Granted I do not do justice to this topic and frankly, it is not my intention to exhaust it. However, I think it is sufficient to begin scaffolding the identity of an entrepreneur in the same way that the identity of a priest, wife or husband might be understood in terms of tenets to which they have avowed. That is to say, one can judge a priest, let’s say, by observing their behaviour in relation to the tenets of priesthood.

Part of the weakness of this particular piece is that I have not clarified what I mean by certain terms. For instance, I presume that the reader will understand my use of sacred is entirely secular. Furthermore, I do not provide a comprehensive exploration of the function of vows, except to say they provide a stencil for judging behaviour. Finally, I do not fully test the weaknesses of my arguments, of which there might be plenty. Notwithstanding these weaknesses, this article serves its purpose of turning the giant wheels for formally defining entrepreneurship.

I find it necessary to repeat that this is a sketch. As such, I invite the reader to challenge and critique the views held, knowing that this might lead to a next and likely more refined iteration. I have also omitted the academic standards and formats, i.e. citations and a bibliography, and might introduce them in the next iteration. Nevertheless, I have taken care to credit authors where necessary.

Once upon a time, two Buddhist monks set out to visit another monastery to learn under a newly ordained priest. One monk was older and more senior, while the other was younger and looked up to their older brother. Both were bold-headed, wore red robes, and carried nothing more than their backs could handle — a strict rule in their teaching.

After days of following trails, asking for directions, wading through thick forests, sleeping under the stars and swatting insects, they finally came to a flooded river. They met a young woman, stranded on their side and scared of crossing. After greetings and pleasantries, she confirmed that the monastery they were looking for was on the other side of the river and that she was headed in the same direction. She would walk with them until they were close enough to find their way if they helped her cross. But there was a problem. The monks had vowed never to touch a female. Another vow, however, was that they would show compassion and help wherever possible.

They politely pardoned themselves from the stranded young lady to debate their conundrum. The younger monk said that they should carry the lady across the river. However, the older monk scolded him, saying it was against their vows. The younger retorted, saying compassion was more important than the rule of touching a female. After a skirmish of words, the younger went back to the young lady and carried her across the river, much to the dismay of the older.

They completed their journey in awkward silence. When they arrived, the older monk, fuming, told the priest that the younger ought to be struck from the monastery for breaking a vow. Calm as a feather floating on a gentle breeze, the younger monk said, “Yes, I broke a precept. I touched a woman and carried her across the river. However, it seems my brother here is still carrying her.”

Vows precede the written word. Yet, they remain a powerful demonstration of commitment. For all our technology and contracts, standing before people and uttering words seems to carry something more than merely writing it down. Even though we sign contracts, we nevertheless say ‘I do’. Moreover, when it comes down to it, our conscience holds us more accountable to the utterance than the contract. “You looked me in the eye and said…” seems more powerful than “you wrote…” It seems plausible, therefore, that vows carry a moral significance. That is to say, they are normative; they compel us to behave in a certain way.

A quick survey of impactful roles leads to vows or precepts that serve as a kind of moral constitution. I have already alluded to marriage, but the same is true for priests, soldiers, and parliamentarians, to name but a few. Strangely, however, entrepreneurs do not take vows or precepts despite their impact. Consequently, entrepreneurs cannot judge themselves or their peers except through the lens of self-interested material gain. In “self-interested material gain”, I am referring to amassing material wealth for one’s benefit in the final analysis.

While I am careful not to imply “selfishness”, i.e. self-interest at the expense of others — even though this is not unusual — two problems come to mind with self-interested material gain:

(i) Firstly, entrepreneurial impact is materially and morally significant. The material significance is a given. Entrepreneurs affect who puts food on the table and how much of it. The moral significance, on the other hand, has been debated in many quarters under stakeholder vs shareholder capitalism. Briefly, the proponents of stakeholder capitalism argue that companies create strong welfarist dependencies in human relationships. That is to say, my children’s welfare depends on my income. All things considered, my income depends on the company. Therefore, my children’s welfare depends on the company. If we consider welfare as morally significant, it follows that the company has a morally significant impact on me, my children and, by extension, anyone whose welfare it affects. In other words, companies must think about all their stakeholders, i.e. the people whose welfare they affect, and not just shareholders. Therefore, if you buy into stakeholder capitalism, it seems to follow that self-interested material gain is insufficient. Entrepreneurs must also be judged in terms of the welfare they produce.

(ii) Secondly, self-interested material gain is insufficient because it can only lead to instrumental value. In philosophy, we distinguish things that have instrumental and intrinsic value. Things with instrumental value are used or converted into other things, ultimately leading to things that are good in themselves or have intrinsic value. For example, money is converted to food, and food to health and/or well-being. While the things with intrinsic value are hotly debated — like health, relationships, happiness, well-being, pleasure — it stands to reason that we draw meaning from ends in themselves more than instruments of ends. Hence, the people who do not invest in thinking about and pursuing things that are ends in themselves unsurprisingly become utterly disillusioned by their material gains. They may become rich and hollow. Therefore, understanding entrepreneurship in terms of self-interested material gain is insufficient.

These two arguments show that entrepreneurs are impactful in society—this is undeniable. However, the way we judge them (and I venture to say, the way we judge ourselves as entrepreneurs) is not only inconsistent, but insufficient. We do not have the instruments to say that it is a good or bad entrepreneur beyond a narrow lens of self-interested material gain, in the same way that we can say that it is a good or a bad priest. My project, therefore, is to begin developing this instrument, aiming for it to capture the practical and the moral role of entrepreneurship.

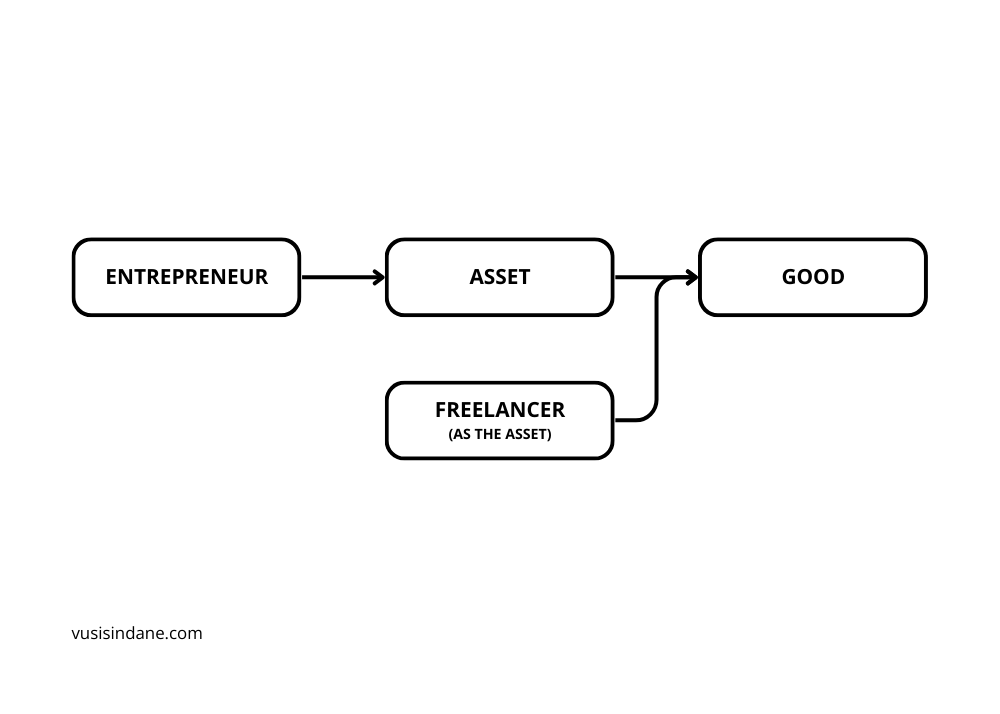

In a previous post (on solopreneurship), I highlighted that freelancers and consultants are not entrepreneurs. The difference is that entrepreneurs build assets that create goods, whereas freelancers and consultants are themselves the asset that creates goods. There are many implications to this subtle but important distinction. Among them is that entrepreneurs can scale their businesses by investing in more assets. However, freelancers and consultants cannot scale themselves because this would lead to burnout. Freelancers and consultants could only optimise their income by getting better clients — the ones who pay more and demand less.

Drawing from this distinction, entrepreneurs invest in assets that create a good. Although I think there is some truth in this definition, it is insufficient. Governments also invest in assets, often at a far more complex or greater scale, leading to greater public goods. However, it would be unusual to call a statesman (not to imply males only) an entrepreneur. It would be better to regard them as astute or demonstrating entrepreneurial traits. It seems to me that the ends for which they work are a distinguishing feature. Entrepreneurs are self-interested, whereas public officials must be altruistic by definition (since they work for the public). The livelihoods that public officials earn ought to be regarded as a reward rather than the ultimate aim.

I therefore stipulate that entrepreneurs are self-interested by definition. In other words, the entrepreneurial telos is realised in terms of the value created for oneself. The value created can be profit. However, I think a better sense of value is wealth. After all, a company could be profitable in terms of its income statement, but destroy wealth in terms of its balance sheet. This is possible when the return on invested capital is less than the weighted average cost of capital (ROIC / WACC) — an insight learned from Dr Mark Lamberti. To this end, entrepreneurship is about creating wealth for oneself, period!

This brings me to two precepts that all entrepreneurs should take.

— (a) I vow to do today what creates a good tomorrow;

— (b) I vow to create wealth and to never destroy it.

As an ethicist in training, I am inclined to wonder whether this precept is sound. My first instinct is to worry about self-interest, as alluded to earlier. It is commonly held in economic theory that when we are all pursuing our self-interest, we inadvertently satisfy other people’s interests. A butcher, in their self-interest to sell meat, supports a farmer whose interest is to raise cattle. The farmer supports the vet. The vet supports researchers — and so on. Ultimately, everyone’s interests are taken care of. This is the Invisible Hand. From an ethical perspective, it is presumed that bad goods and actors will lose demand, which mitigates the proliferation of bad products and unethical behaviour. In other words, the invisible hand system self-corrects.

This arrangement incorrectly presumes the durability of perceived causal relationships. For instance, suppose that some goods show positive results in the short term but turn out to be, in fact, bad in the long run. Such goods might not be detected as bad, at least not in the short term, leading to continuous support at people’s eventual peril, like social media, diets and so-called ethical drugs.

The invisible hand also presumes that we make sound judgments in our best interest. However, behavioural economists and psychologists like Daniel Kahneman, in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, and Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book, Nudge, raise questions about the degree to which we can make rational choices. They argue, to the contrary, that we read cues in the environment, and instead of using logic, we use what Rory Suther, in his book Alchemy, calls psycho-logic. We wade through biases and psychological forces like social proof, shame, and scarcity to make decisions. Pushing this view to its logical conclusion suggests that we do not, for the most part, make rational decisions. Instead, we confabulate; we post-rationalise the decisions our minds have already made unbeknownst to us. This further undermines the idea that the invisible hand is self-correcting because it suggests that we are more at the mercy of social and market forces than our ability to make decisions. We are not autonomous decision-makers.

To summarise, the doctrine of self-interest is grounded in the idea that each individual knows what is good for them and can make decisions in that regard, i.e. we are autonomous decision-making agents. On the other hand, behavioural economists (it seems) challenge this notion of autonomy in decision making by arguing that we are more at the mercy of biases and psychological forces than we think. We are nudged more than we realise. This brings us to a discussion about ethics. While the proposed precepts, so far, guide the work of an entrepreneur, i.e. to create wealth through investing in assets, this should not be presumed to be good in itself. Behavioural economics demands that we appreciate our fallibility and the extent to which we can be taken advantage of. A profitable enterprise may, in fact, be harmful in society, and therefore draw ethical concern.

I am therefore drawn to the ethics of Ubuntu. Although Prof. Thaddeus Metz’s formulation of Ubuntu is debated, it is nevertheless analytically coherent and provides a sufficient foundation for my purpose. He postulates that [roughly] under Ubuntu Ethics, an action is right insofar as it promotes the capacity to harmonise. The capacity to harmonise is grounded in the principles of identity and solidarity. Identity refers to seeing oneself and others as co-existential, that is to say, “our fate is inseparable.” It is this principle, [I postulate] that the phrase I am because you are seeks to express. It follows that if our fate is inseparable, I must always consider your well-being in my undertakings — I must act in solidarity.

These two principles, identity and solidarity, explain the nuances of African social intercourse. For example, when you are about to embark on a journey, I should not allow you to leave my home without a meal. When you arrive at my home, I should receive and harmonise with you before we get into the purpose of your visit. Hence, it is normal for Africans to spend hours finding each other at a personal level before getting into their meeting agenda.

Some scholars might confuse this ethic with Utilitarianism, which postulates that an action is right insofar as it maximises the good for the many. Ubuntu is not about maximising the good, even though it is often good-maximising in the utilitarian sense; it is about promoting the capacity to harmonise. There are axiological and functional differences here. The axiological difference is that utilitarianism requires a principle of utility — that is to say, a definition of what is good. Classical utilitarianism holds that pleasure or happiness is the ultimate good. Therefore, an act is good insofar as it maximises happiness or pleasure. On the other hand, Ubuntu is not interested in happiness; it is interested in community.

Secondly, the functional difference — and this is specific to Prof Metz’s formulation — is that Ubuntu is concerned with promoting the capacity to create harmony, more than harmony itself. Hence, it is called a modal theory of Ubuntu. This is like realising importance of water. However, to grasp it, one must use a container. Similarly, harmony is important, but to achieve it, one must focus instead on promoting the capacity to generate harmony more than harmony itself. Seen this way, we can distinguish between Ubuntu qua [in its place as] the ethic, and Ubuntu qua the practice. An unruly person, for instance, may be regarded as lacking Ubuntu qua the practice but retain their status and be deserving of Ubuntu insofar as they have the capacity to harmonise. Hence, it is said, “Umuntu akalahlwa” — you cannot throw a person away (presumably regardless of the bad they have caused).

This might seem outrageous and farfetched, especially in a society that is diluted of the principles of Ubuntu. However, this is essentially what happened in the TRC, during the transition from Apartheid to a Democratic South Africa. The underlying ethic, as championed by Bishop Desmond Tutu, was in keeping with the principles of Ubuntu. Although the perpetrators of Apartheid had committed atrocities, in the framework of Ubuntu, this did not remove their capacity to harmonise. It was thus believed that a truth and reconciliation commission would reconstitute and promote this capacity.

Of interest to me is the misplaced notion of self-interest, which I alluded to in the previous section. Briefly, let me add that self-interest overlooks the idea that our identity is formed in relation to others. In his book On Human Nature, Sir Roger Scruton distinguishes an I from an it, that is to say, a subject from a thing. As human beings, we are subjects precisely because we not only experience the world, but we can reflect on that experience. In other words, we can act and, in acting, think about the rightness or wrongness of our action. This makes us moral agents. Moreover, in our existence, we realise that the other is something like me. In other words, the other is a moral agent — they are also an I and not an it. In this respect, human relations are an intercourse of rights, respect, dignity and responsibilities. Furthermore, in observing oneself and others as subjects enjoined in moral life, we draw distinctions and find similarities from which we form our aspirations in the flesh and meaning in the moral realm. All of this is to say, self-interest is itself inconceivable without the other.

For this reason, I think Ubuntu serves as an important antidote to blind self-interest insofar as it reminds us that we are inseparable. Therefore, we ought to find ways to promote our coexistence by promoting the capacity to harmonise. As such, I think we have thus arrived at the final precept:

— (c) Above all, I vow to nurture the capacity for harmony in myself and others.

In this section, I will briefly explore the precepts discussed above and perhaps expound upon some of the theories. What comes to mind immediately is that the precepts take on a Kantian Ethics structure. Immanuel Kant is famous for contributing the idea that what makes us moral agents is our rationality. It is from this rationality that we set and pursue goals — we are autonomous (or self-legislating). It follows that setting goals and then acting in a way that undermines, or being in a context (like slavery or addiction) where we are unable to self-legislate, undermines our humanity — it is heteronomous.

However, if we are free to set whichever goals we choose, it is easy to imagine that we can run into problems. For instance, we can inhibit others from doing the same. To avoid this, Kant proposes a golden rule that may not be broken under any circumstances — what he calls the Categorical Imperative. He formulates that we must always act in such a way that the guiding principle of our action can be universally acceptable. Moreover, we must always act in a way that respects the humanity in ourselves and others. Outside these commandments, as it were, we are free to set and pursue whatever other goals we see fit.

As you can see, the Kantian Ethical Structure is like a patch of land where we are free to act in whatever way we want, provided it is within the boundaries of the Categorical Imperative. In my proposed precepts, the Entrepreneur is similarly avowed to the creation of goods and wealth (even for self-interest), provided they are mindful of their interconnectedness with the world around them, and in this mindfulness promote harmony.

These African Entrepreneurs — as I dare call them — would find themselves in constant tension in South Africa. They would struggle to make sense of the stark contrast between Alexandra and Sandton in Johannesburg, and Masiphumelele and Lake Michelle in Cape Town (and many similar examples throughout the country). Their challenge would not be so much about the differences in material, but regarding the prevailing disharmony and the continued desecration of the capacity to create it. Where the current crop of entrepreneurs cleanse themselves with the dirty cloth of philanthropy, which seemingly makes no difference, the African Entrepreneur, guided by principles of Ubuntu, would have a more nuanced approach, which I will explore below.

Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson, in their seminal papers, studied wealth creation during the colonial era and showed a causal relationship between institutional formations and prosperity. In other words, prosperity is more a function of context than individual brilliance. Another Laureate, Joseph Stiglitz, argued that some of the greatest contributors in society, like Albert Einstein, Alan Turing, were not the greatest income-earners despite their unmatched contributions. Instead, business people, who hardly contributed anything by comparison, commanded the highest income, mostly by attending to market forces and taking advantage of institutional formations. Therefore, wealth creation is more of a function of context.

This brings the proposed precepts into sharp focus, beginning with the capacity to harmonise. Harmony is not about creating the same outcomes. However, it is about creating the conditions for people to realise their potential in their chosen identity. As it stands, some identities, if chosen, can lead to one’s peril because they are not viable economically, even if they add value by other non-commercial means. To this end, a system that only values economic value undermines humanity. Ubuntu has been capable of dealing with these matters because it is not fixated on money; it is about harmony. When people gather at a family function, some contribute food, others money, and others show up to play their roles as elders or zealous young men. It is in this spirit that Ubuntu accommodates a pluralist society where many forms of value can coexist. Therefore, the goal is not to create the same outcomes. Instead, it is to promote the capacity to harmonise — it is to work on the institutions that create harmony at all levels of the system, personally, within the family context, and in society.

Guided by the precepts, therefore, the African entrepreneur (I speculate) would hold these general views in the South African context:

(a) I vow to do today what creates a good tomorrow: The African Entrepreneur would discourage unproductive consumption. Consuming today without a care about what happens tomorrow makes things worse tomorrow. In tandem with education, they would prohibit (or at least encourage the prohibition) of debt for consumption. They would encourage people to use their disposable income and labour to create assets, thereby creating a better tomorrow. This is in stark contrast to many (although not all) brands of philanthropy that deepen a dependency on the giver, thereby raising their status as a benefactor, rather than liberating the beneficiary from their plight and restoring their autonomy.

(b) I vow to create wealth and never to destroy it: Moreover, the African Entrepreneur would (themselves) invest heavily in people who pass muster in the first precept. They would invest with the belief that, at a higher level (if one could say that), is itself doing today what creates a better tomorrow. In other words, they would cleave themselves from the shortsighted view that wealth is only on the balance sheet. They would know that the balance sheet only indicates instrumental value and that intrinsic value is in the relationships enjoyed in harmony with others. The African Entrepreneur would therefore invest in people committed to creating a better tomorrow, businesses that promote autonomy, and institutions that encourage social cohesion.

(c) Above all, I vow to nurture the capacity for harmony in myself and others: There is a prevailing understanding that companies are legal persons and economic instruments. This view is enshrined in law, where doctrines like limited liability seem justifiable beyond their ethical implications. Inasmuch as Limited Liability and other statutes have encouraged investment and wealth creation, they have also protected unethical practices like hoarding wealth or dumping companies without due consideration to the people affected. Where proponents of private property might argue that one should do as one pleases with one’s property, some proponents of stakeholder capitalism highlight, as mentioned earlier, that companies cause dependencies among people and therefore create the conditions for ethical considerations beyond mere legalities.

In other words, the African Entrepreneur, although guided by the principles of sound economics, is deeply rooted in the desire to promote harmony in oneself and others to generate the broadest realisation of potential. Crucially, this is more about sustainability in the long run than maximising returns in the short term.

I have explored the importance of vows in forming a moral constitution. I have observed that roles of import are usually grounded or governed by vows and precepts, including marriages, parliamentarians, the military, doctors and so on. However, entrepreneurs do not take precepts despite having immense impact in society.

I have therefore sought to draft precepts (or tenets) that an entrepreneur may take and hold sacred. Initially, I proposed two vows directly related to the primary role of the entrepreneur, namely, to create wealth. It follows from the aim of creating wealth that one must always act today to create a good tomorrow. This forms the first two precepts that I will restate below. However, the self-interested nature of commerce raised moral concerns that I softened with Ubuntu Ethics. Thus, I arrived at three precepts, namely:

(a) I vow to do today what creates a good tomorrow

(b) I vow to create wealth and never to destroy it

(c) Above all, I vow to nurture the capacity for harmony in myself and others

Share: If you know someone who should read this post, please share it with them.

If you enjoyed this post, subscribe to get notified about the next post and to receive additional tools like book recommendations, checklists, and tested frameworks.

Subscribe to a weekly dose of ideas about strategy, ethical leadership and innovation.